Political realignment in Lebanon ahead of elections

Rami Rayess / The Arab Weekly

30 يناير 2018

Almost 100 days separate Lebanon from its parliamentary elections, the first since 2009. The current parliament’s mandate has been extended twice on the pretext of security concerns. Now, despite those extensions and immediacy of the coming vote, suspicions are growing that the elections may be delayed as Beirut’s political class seeks to avoid being held accountable for past failures.

The garbage crisis significantly widened the yawning gulf between the people and those elected to govern them. Likewise, persistent power failures that blight all of Lebanon, despite the millions of dollars lavished upon the sector since the 1990s, have done little to endear the country’s politicians to the people.

Abroad, Hezbollah continues its foreign adventures, risking calamity for Lebanon with every advance against a foreign power. Within the country, the infrastructure is collapsing as hundreds of thousands of refugees exacerbate the situation further.

For these reasons and many more, Lebanon’s political parties would prefer to avoid the direct judgment of the electorate or are seeking refuge from the public glare within a series of shifting political alliances.

The Ministry of Interior announced its readiness to have elections on May 6. Candidates can officially announce their candidacy by February 6. The new electoral law mandates that candidates be organised on lists. Candidates are prohibited from running as independents.

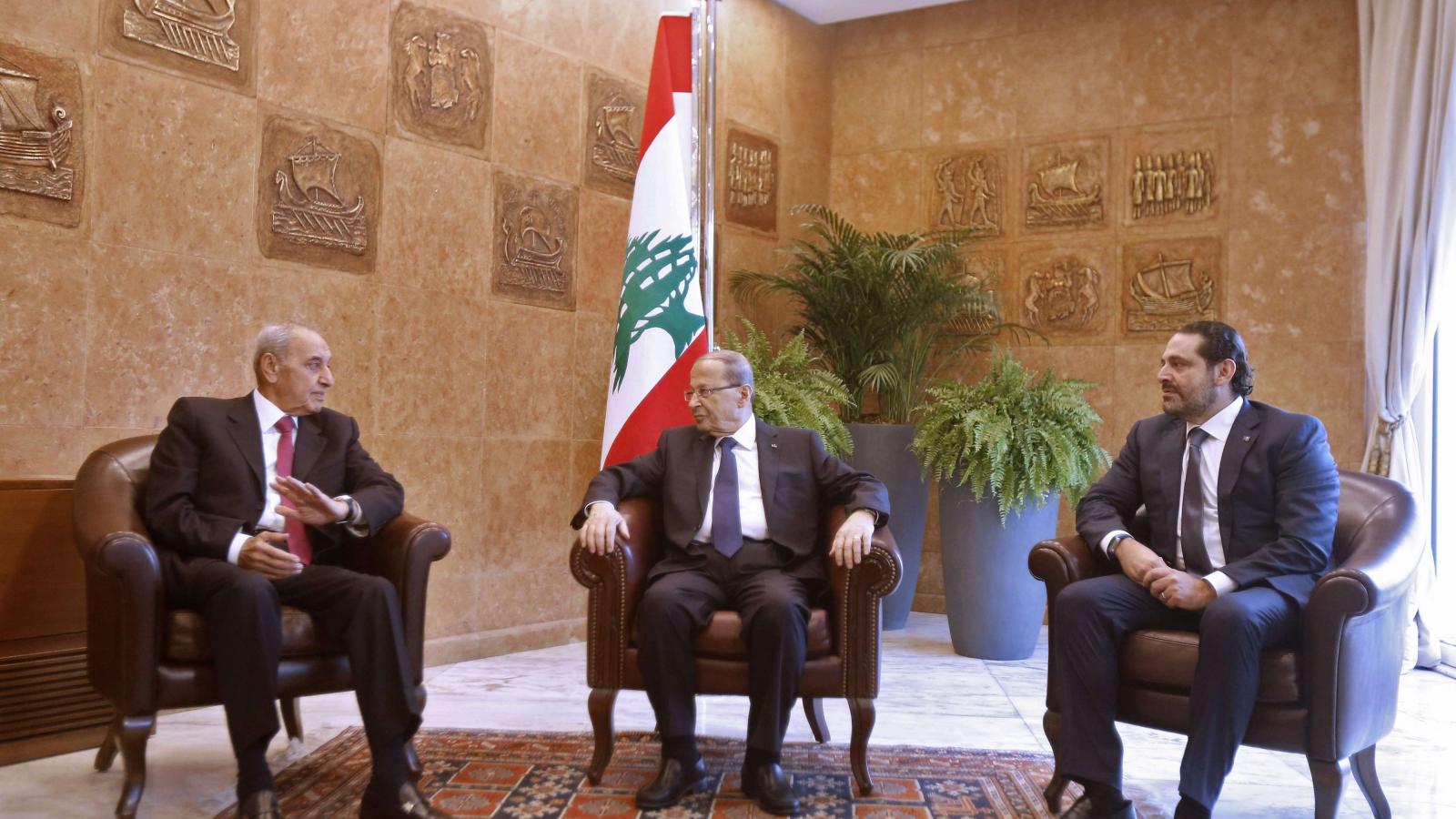

It’s a situation that encourages alliances. In recent weeks, much talk has been given to a potential alliance of the “big five” — the Free Patriotic Movement (FPM), which is the party of President Michel Aoun; the Future Movement, which is the party of Prime Minister Saad Hariri; the Amal Movement, the party of the Speaker Nabih Berri; the Progressive Socialist Party headed by Walid Jumblatt; and Hezbollah.

In a recently televised interview, Jumblatt said that such a group would lead to the isolation of other, smaller groups, such as the Lebanese Forces. Lebanon’s experience of having various political parties sidelined achieved nothing but furthering the cycles of violence that have dogged the country, he said. Preserving stability was a preferred policy for Jumblatt.

What appears certain, no matter what happens before the election, is that Lebanon’s traditional system of political division appears over. Previously, Lebanon’s political groups were lumped together into two broad camps: the March 8 and March 14 alliances. It’s a system that appears to have an ingrained failure within its framework, with repeated shortcomings failing to advance the Lebanese cause.

Despite this, there is increasing inferences that Saudi Arabia may be considering holding the March 14 group together, hoping that it can heal the ruptured alliance between its principal Lebanese allies, Hariri and leader of the Christian Lebanese Forces Samir Geagea. However, with bad blood boiling between the two since Hariri’s unexpected sojourn last November in Saudi Arabia, plus the ostensible rapprochement between him and an ally close to the March 8 group — Aoun — the future of the former alliance appears dubious.

Irrespective of any political detente between prime minister and president, is Aoun’s relationship with Hezbollah. The group has been a staunch ally of his since 2006, with the president rewarding its support by publicly downplaying its role in the Syrian war and justifying its retention of weapons.

Clearly, for this and countless other reasons, this is a problem for Hariri and not least because of how it might play in Riyadh. Following his recent abrupt resignation announcement and the deterioration of his relations with Saudi Arabia, Hariri cannot afford either a direct or indirect alliance with Hezbollah, a group accused by the Saudis of interfering in the Yemen war in support of the Houthis.

Amid this shuffling of alliances and deal-making, new civil society groups are emerging, gathering their forces to participate in the upcoming vote. While an unknown quantity, their involvement looks to add an extra challenge to the elections. It could widen the political appeal of the parliament beyond the stale clique of old faces with the possibility of turning huge parliamentary blocs into smaller dispersed heterogeneous groups.

Despite these early manoeuvres, confident predictions are hard to make. Once the lists are officially announced and the nominees known, more will become clear. For now, all we have is speculation. What is certain is that the new electoral system is an unpredictable adventure for Lebanon’s ailing and calcified democracy.

Suspicions are growing that the elections may be delayed as Beirut’s political class seeks to avoid being held accountable for past failures.

عن أمل جنبلاط المتجدد: لبنان يستحق النضال

عن أمل جنبلاط المتجدد: لبنان يستحق النضال

صحافيون أم عرّافون!

صحافيون أم عرّافون!

ماذا يجري داخل أروقة بيت الكتائب المركزي؟

ماذا يجري داخل أروقة بيت الكتائب المركزي؟

عن الخرائط التي تُرسم والإتفاقات التي تتساقط!

عن الخرائط التي تُرسم والإتفاقات التي تتساقط!

“الإنحراف في الحياة”/ بقلم كمال جنبلاط

“الإنحراف في الحياة”/ بقلم كمال جنبلاط

هاشتاغ #صار_الوقت يحل أولاً في حلقة جنبلاط

هاشتاغ #صار_الوقت يحل أولاً في حلقة جنبلاط

طاولة نقاش عن أزمة الصحافة في جامعة AUST

طاولة نقاش عن أزمة الصحافة في جامعة AUST

عبدالله: ليظهر لنا وزير مكافحة الفساد حرصه في صفقات البواخر والفيول

عبدالله: ليظهر لنا وزير مكافحة الفساد حرصه في صفقات البواخر والفيول

عبدالله: غريب أمر وزارة مكافحة الفساد!

عبدالله: غريب أمر وزارة مكافحة الفساد!

Comment to Uri Avnery: How Sad What Is Looming Ahead

Comment to Uri Avnery: How Sad What Is Looming Ahead

“Not Enough!”

“Not Enough!”

… لمن لم يقرأ يوسف البعيني/ بقلم وسام شيّا

… لمن لم يقرأ يوسف البعيني/ بقلم وسام شيّا

كمال جنبلاط في مولده الأول بعد المائة: تعاليمه وأفكاره ما زالت الحلّ/بقلم عزيز المتني

كمال جنبلاط في مولده الأول بعد المائة: تعاليمه وأفكاره ما زالت الحلّ/بقلم عزيز المتني

رئيس حزب/ وليس (… سابقاً)/ بقلم د. خليل احمد خليل

رئيس حزب/ وليس (… سابقاً)/ بقلم د. خليل احمد خليل

التوازن السياسي في لبنان

التوازن السياسي في لبنان

لبنان… مشاريع انقلابية مؤجلة

لبنان… مشاريع انقلابية مؤجلة

جنبلاط وحَمَلة أختام الكاوتشوك

جنبلاط وحَمَلة أختام الكاوتشوك

Le Liban est un symbole de tolérance

Le Liban est un symbole de tolérance

Our Automated Future

Our Automated Future

The True Origins of ISIS

The True Origins of ISIS

Les Misérables vs. Macron

Les Misérables vs. Macron

عذراً أيها المعلم/ بقلم مهج شعبان

عذراً أيها المعلم/ بقلم مهج شعبان

رساله الى المعلم / بقلم ابو عاصم

رساله الى المعلم / بقلم ابو عاصم

إلى روح القائد والمعلم كمال جنبلاط/ بقلم أنور الدبيسي

إلى روح القائد والمعلم كمال جنبلاط/ بقلم أنور الدبيسي

أسرار وعناوين الصحف ليوم الجمعة 14 كانون الاول 2018

أسرار وعناوين الصحف ليوم الجمعة 14 كانون الاول 2018