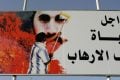

Daesh makes America lean toward Assad

Michael Young/ The Daily Star

10 ديسمبر 2015

In the past four and a half years the Obama administration has argued that its decision not to intervene in Syria has been motivated by a desire to pursue only the vital interests of the United States. Fair enough. Syria has become a maelstrom that has sucked in all countries, without any end in sight.

However, almost daily President Barack Obama is being drawn further into the conflict in one way or the other. We may be far from a major deployment of American ground forces, but that was never a realistic alternative anyway, only a bogeyman the White House held up to avoid taking any action whatsoever in Syria. Is there something the president could have done to avoid the deterioration there, while also advancing U.S. interests?

Obama’s priority in Syria remains the defeat of Daesh (ISIS). Recall how the president won re-election in 2012 after making the assassination of Osama bin Laden a centerpiece of his campaign. A resolution of the Syrian war seems almost to be an appendage of this objective, and is why the U.S. administration has been so inconsistent on the future of Bashar Assad’s regime.

Take Secretary of State John Kerry’s remarks a week ago in Belgrade, at a meeting of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe. Kerry remarked, “I think we know it, that without the ability to find some ground forces that are prepared to take on [Daesh], this will not be won completely from the air.” When asked if that meant Western and Arab forces, the secretary replied that he meant Syrian and Arab forces.

Ironically, this echoed Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov’s statements in the past that the Syrian government and opposition had to join forces to defeat Islamist extremist groups. Not that Kerry was so specific. However, coming at a time when the United States has advised opposition groups meeting in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, to use “creative language” when discussing Assad’s fate, it suggested that Washington’s sense of priorities are very much Daesh first and Assad second.

That’s the wager of the Syrian president, Russia and Iran. They could not have wished for a better development than the San Bernardino massacre, soon after the slaughter in Paris brought about a change in the French government’s attitude toward Assad. But if terrorism is the new urgency, what that means is that the more profound causes of the Syrian conflict will continue to be put on the backburner by Western governments.

One longs for the day when Obama will apologize for having dismissed the Syrian conflict as “somebody else’s civil war.” It is odd that none of his foreign policy advisors ever bothered to pick up a book on the country, for they would have seen that whatever affects Syria rarely fails to impact on the Arab world.

As Patrick Seale wrote in the introduction to a new edition of his classic “The Struggle for Syria,” “Given its geographical position, its pan-Arab credentials, its ideological fertility, and the vitality, skills and political passions of its people, Syria could not escape the attentions of others. Each sought to control it or, failing that, to deny its control to others on the tacit premise that to exercise dominant influence over Syria was to hold rival combinations at bay.” That Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi grasped this before Obama did says a lot about attitudes in the White House.

Yet Obama still does not have, nor does he want to have, a Syria-centric policy. His overriding objective is to “defeat” Daesh, even as he has not adequately explained why the logic he applied in Iraq should not apply to Syria. In Iraq the administration understood early on last summer that a vital component in defeating Daesh was to address the frustrations of the Sunni community. It helped remove Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki from office on those grounds, in the hope that Haider al-Abadi would open up to the Sunnis. Yet in Syria its fear of a vacuum in Damascus is so great, that it has failed to address Sunni discontent and seems surprised that the vacuum it helped perpetuate because of this facilitates more extremism.

Obama’s strategy in Syria is to keep Assad in place until a managed transition is effected, so that what emerges is a broad Syrian government willing to fight Daesh. But the problem is that for as long as Assad is in place, Daesh and other groups, such as the Nusra Front, will continue to attract followers.

No one seems to know how to cut this Gordian Knot, to the extent that the Americans are now advising the rebels to be flexible. The Russians are right to use this impasse as leverage to slowly but surely re-legitimize Assad rule. The Western states seem especially eager to make concessions, even though Assad is, militarily, the weaker party in the ongoing conflict.

That was one purpose of Vladimir Putin’s decision to enter the fray in Syria. By doing so he reversed any potential desire of the Americans and Europeans to turn the tide in the conflict. So reluctant would they be to confront the Russians, he gambled, that all measures that might decisively benefit the opposition, such as the creation of a safety zone along the Turkish border, would be shelved. Not surprisingly the current tensions between Moscow and Ankara touch on this, with Russia seeking to neutralize Turkey’s ability to arm Assad’s enemies.

What are Obama’s aims? Would things not have been better had he intervened early in favor of Assad’s enemies, so they could overthrow a barbaric regime and prevent a radicalization that led to groups such as Daesh? Yet his single-minded refusal to “get involved” has created a situation compelling Obama to do just that. If the end-result is Assad’s political survival, the president will have to explain how American interests have been served.

عن أمل جنبلاط المتجدد: لبنان يستحق النضال

عن أمل جنبلاط المتجدد: لبنان يستحق النضال

صحافيون أم عرّافون!

صحافيون أم عرّافون!

ماذا يجري داخل أروقة بيت الكتائب المركزي؟

ماذا يجري داخل أروقة بيت الكتائب المركزي؟

عن الخرائط التي تُرسم والإتفاقات التي تتساقط!

عن الخرائط التي تُرسم والإتفاقات التي تتساقط!

“الإنحراف في الحياة”/ بقلم كمال جنبلاط

“الإنحراف في الحياة”/ بقلم كمال جنبلاط

هاشتاغ #صار_الوقت يحل أولاً في حلقة جنبلاط

هاشتاغ #صار_الوقت يحل أولاً في حلقة جنبلاط

طاولة نقاش عن أزمة الصحافة في جامعة AUST

طاولة نقاش عن أزمة الصحافة في جامعة AUST

عبدالله: ليظهر لنا وزير مكافحة الفساد حرصه في صفقات البواخر والفيول

عبدالله: ليظهر لنا وزير مكافحة الفساد حرصه في صفقات البواخر والفيول

عبدالله: غريب أمر وزارة مكافحة الفساد!

عبدالله: غريب أمر وزارة مكافحة الفساد!

Comment to Uri Avnery: How Sad What Is Looming Ahead

Comment to Uri Avnery: How Sad What Is Looming Ahead

“Not Enough!”

“Not Enough!”

… لمن لم يقرأ يوسف البعيني/ بقلم وسام شيّا

… لمن لم يقرأ يوسف البعيني/ بقلم وسام شيّا

كمال جنبلاط في مولده الأول بعد المائة: تعاليمه وأفكاره ما زالت الحلّ/بقلم عزيز المتني

كمال جنبلاط في مولده الأول بعد المائة: تعاليمه وأفكاره ما زالت الحلّ/بقلم عزيز المتني

رئيس حزب/ وليس (… سابقاً)/ بقلم د. خليل احمد خليل

رئيس حزب/ وليس (… سابقاً)/ بقلم د. خليل احمد خليل

التوازن السياسي في لبنان

التوازن السياسي في لبنان

لبنان… مشاريع انقلابية مؤجلة

لبنان… مشاريع انقلابية مؤجلة

جنبلاط وحَمَلة أختام الكاوتشوك

جنبلاط وحَمَلة أختام الكاوتشوك

Le Liban est un symbole de tolérance

Le Liban est un symbole de tolérance

Our Automated Future

Our Automated Future

The True Origins of ISIS

The True Origins of ISIS

Les Misérables vs. Macron

Les Misérables vs. Macron

عذراً أيها المعلم/ بقلم مهج شعبان

عذراً أيها المعلم/ بقلم مهج شعبان

رساله الى المعلم / بقلم ابو عاصم

رساله الى المعلم / بقلم ابو عاصم

إلى روح القائد والمعلم كمال جنبلاط/ بقلم أنور الدبيسي

إلى روح القائد والمعلم كمال جنبلاط/ بقلم أنور الدبيسي

أسرار وعناوين الصحف ليوم الجمعة 14 كانون الاول 2018

أسرار وعناوين الصحف ليوم الجمعة 14 كانون الاول 2018