Even a ‘Diplomat’s Diplomat’ Can’t Solve Syria’s Civil War

David Kenner/ The atlantic

27 نوفمبر 2018

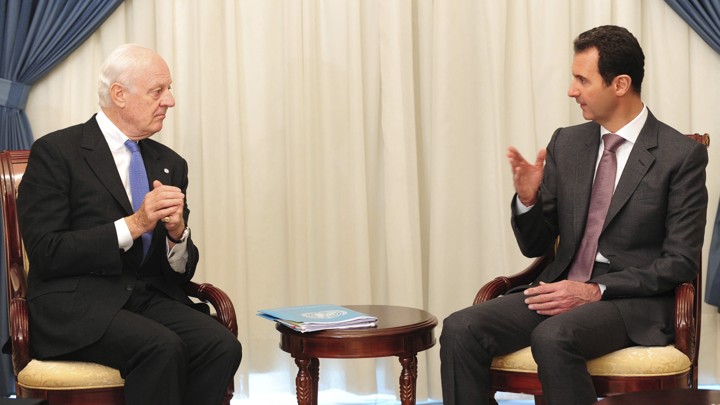

If the only thing you knew about Syria came from the United Nations Special Envoy Staffan de Mistura’s briefing to the Security Council this month, you might assume that dramatic events were afoot. An important meeting had taken place in Istanbul, he said, while equally vital summits in Astana, Kazakhstan, and of the G-20 countries in Buenos Aires were in the offing. The work under way was “absolutely urgent,” he told the council, and the coming weeks “will be of crucial importance.”

Outside of such briefings, however, there is no suspense about the outcome of the Syrian war. President Bashar al-Assad, with the help of his Russian and Iranian allies, has used brute force to pacify the majority of the country. Half of the Syrian population has fled their homes, and the violence has reached such a fever pitch that the United Nations has lost count of the number of lives claimed by the war. The prospects for de Mistura’s peace plan are nonexistent—Assad is not about to relinquish his hard-won battlefield gains at the negotiating table.

The Swedish Italian diplomat’s tenure is emblematic of the international community’s struggles to grapple with Syria. His term provides a window into the forces that have made the conflict so resistant to diplomacy, and has served as a launching point for a debate among analysts and would-be peacemakers about diplomats’ roles in resolving the world’s worst crises.

De Mistura is the diplomat’s diplomat. He is known for his dapper suits and pince-nez spectacles, speaks seven languages, and has worked for the United Nations over a four-decade career that has taken him from Sudan to Kosovo, from Iraq to Afghanistan. When he leaves his post in December, he will have served as the face of UN diplomacy in Syria for more than 1,600 days. The combined tenure of his two predecessors, by comparison, was roughly half that long. His defenders often refer to this fact as a point in his favor, praising his perseverance in such a thankless task. (De Mistura, through a spokesman, declined an interview request for this article.)

To his detractors, however, de Mistura’s only legacy is presiding over an effort that has grown ever more divorced from reality. Mouin Rabbani, who briefly served as the head of de Mistura’s political-affairs unit, described the diplomatic track that de Mistura oversees as a Syrian version of the Israeli-Palestinian “peace process”—an effort that exists mainly in the minds of a cottage industry of diplomats. Nearly every cease-fire championed by de Mistura has collapsed, and he proved largely powerless to negotiate the entry of aid to areas besieged by Assad’s government. He is accused of lending his imprimatur to a diplomatic charade, even as the Syrian government and its allies conducted a scorched-earth policy against rebel-held parts of the country.

De Mistura came to office in summer 2014, when U.S. and European diplomats were coming to terms with the fact that their initial assumptions about the course of the Syrian war had been badly misguided. Assad’s regime had proved considerably stronger than many had predicted. De Mistura’s predecessor, Lakhdar Brahimi, advised the Syrian president in their first meeting that he should adhere to a recent international communiqué and declare that he was willing to resign if it was in the country’s best interest, said Mokhtar Lamani, the head of Brahimi’s office in Damascus. Relations were strained for the rest of Brahimi’s tenure.

From the start, de Mistura vowed to cultivate better ties with Damascus. “What he wanted to do is build trust with the Russians and the regime,” says Wa’el Alzayat, a former State Department official who worked on Syria with de Mistura. “His approach was don’t be confrontational; don’t call out the Russians and the regime for their violations.”

In his public statements, de Mistura struck a relentlessly optimistic note about the possibility of a diplomatic breakthrough. He touted a potentially “historic junction” for peace in 2016, said that the train for diplomacy was “warming up its engine” in 2017, and vowed to “strike while the iron is hot” for negotiations in 2018. Meanwhile, he kept repeating a mantralike assertion that there was no military solution: “The one constant in this violently unpredictable conflict is that neither side will win,” he told the Security Council in September 2016.

Assad never got the memo. De Mistura’s signature initiative early in his tenure was an effort to negotiate a “freeze” to the fighting in Aleppo, where pro-Assad forces were attempting to besiege the rebel enclave in the east of the city. As the government offensive continued apace, he was forced to repeatedly define-down success—moving from an attempted cease-fire in the entire province, to a six-week suspension of aerial and artillery bombardment in the city, and then finally to a cease-fire in a single neighborhood. Eventually, it was military men who determined the fate of Aleppo: The city was retaken by the government after a grinding offensive left thousands dead and whole districts in ruins.

In his briefings to the Security Council, de Mistura described a future in which the de-escalation zones resulted in a decrease in violence. In reality, they allowed the Syrian government and its allies to temporarily shift forces away from those regions and concentrate on pacifying other ones. Once those areas had been retaken, pro-Assad forces renewed their assault on the de-escalation zones.

De Mistura’s final diplomatic initiative has been the creation of a committee to draft a new Syrian constitution. For the past year, he has attempted to launch the initiative with participation from both opposition and government members, and is staying in office until December to determine whether there is any prospect for success. Even if the committee is formed, its ultimate goal of free and fair elections leading to a political transition remains as far away as ever. In a parting shot at de Mistura, the Syrian government daily al-Thawra accused him of conspiring with “terrorists.” “You have arrived at the wrong address, and knocked on the wrong door, and come at the wrong time,” it said.

The hopelessness of these diplomatic efforts has led to calls for the incoming special envoy, Geir Pedersen, to scrap the entire process. De Mistura’s defenders argue that public condemnations of those standing in the way of peace will do nothing to change the reality on the ground, and that admitting defeat would hardly save a single life.

“The argument that by stopping the political process, you can reinvigorate it—I don’t think that’s the case at all,” says Nikolaos van Dam, the former Dutch envoy for Syria. “It doesn’t at all mean your successor has a mission which is a little bit more possible.”

By maintaining the political process at all costs, critics would argue, diplomats risk becoming accomplices to the very abuses they are trying to stop.

“At some point, [diplomats] need to speak out in ways that make those standing in their way uncomfortable,” said Alzayat, the former State Department official. “At the end of the day, if they are really committed to the work they are doing, they need to put themselves out there and resign.”

At the height of the onslaught in Aleppo, de Mistura ended his briefing to the Security Council by explaining why he would stay in office. “Any sign of me resigning would be a signal that the international community is abandoning Syrians,” he said.

Two years later, there are few Syrians of any political persuasion who labor under the illusion that the international community, specifically the United Nations, can affect the course of their lives. And there are few diplomats who would honestly say that they have a blueprint for changing that reality.

عن أمل جنبلاط المتجدد: لبنان يستحق النضال

عن أمل جنبلاط المتجدد: لبنان يستحق النضال

صحافيون أم عرّافون!

صحافيون أم عرّافون!

ماذا يجري داخل أروقة بيت الكتائب المركزي؟

ماذا يجري داخل أروقة بيت الكتائب المركزي؟

عن الخرائط التي تُرسم والإتفاقات التي تتساقط!

عن الخرائط التي تُرسم والإتفاقات التي تتساقط!

“الإنحراف في الحياة”/ بقلم كمال جنبلاط

“الإنحراف في الحياة”/ بقلم كمال جنبلاط

هاشتاغ #صار_الوقت يحل أولاً في حلقة جنبلاط

هاشتاغ #صار_الوقت يحل أولاً في حلقة جنبلاط

طاولة نقاش عن أزمة الصحافة في جامعة AUST

طاولة نقاش عن أزمة الصحافة في جامعة AUST

عبدالله: ليظهر لنا وزير مكافحة الفساد حرصه في صفقات البواخر والفيول

عبدالله: ليظهر لنا وزير مكافحة الفساد حرصه في صفقات البواخر والفيول

عبدالله: غريب أمر وزارة مكافحة الفساد!

عبدالله: غريب أمر وزارة مكافحة الفساد!

Comment to Uri Avnery: How Sad What Is Looming Ahead

Comment to Uri Avnery: How Sad What Is Looming Ahead

“Not Enough!”

“Not Enough!”

… لمن لم يقرأ يوسف البعيني/ بقلم وسام شيّا

… لمن لم يقرأ يوسف البعيني/ بقلم وسام شيّا

كمال جنبلاط في مولده الأول بعد المائة: تعاليمه وأفكاره ما زالت الحلّ/بقلم عزيز المتني

كمال جنبلاط في مولده الأول بعد المائة: تعاليمه وأفكاره ما زالت الحلّ/بقلم عزيز المتني

رئيس حزب/ وليس (… سابقاً)/ بقلم د. خليل احمد خليل

رئيس حزب/ وليس (… سابقاً)/ بقلم د. خليل احمد خليل

التوازن السياسي في لبنان

التوازن السياسي في لبنان

لبنان… مشاريع انقلابية مؤجلة

لبنان… مشاريع انقلابية مؤجلة

جنبلاط وحَمَلة أختام الكاوتشوك

جنبلاط وحَمَلة أختام الكاوتشوك

Le Liban est un symbole de tolérance

Le Liban est un symbole de tolérance

Our Automated Future

Our Automated Future

The True Origins of ISIS

The True Origins of ISIS

Les Misérables vs. Macron

Les Misérables vs. Macron

عذراً أيها المعلم/ بقلم مهج شعبان

عذراً أيها المعلم/ بقلم مهج شعبان

رساله الى المعلم / بقلم ابو عاصم

رساله الى المعلم / بقلم ابو عاصم

إلى روح القائد والمعلم كمال جنبلاط/ بقلم أنور الدبيسي

إلى روح القائد والمعلم كمال جنبلاط/ بقلم أنور الدبيسي

أسرار وعناوين الصحف ليوم الجمعة 14 كانون الاول 2018

أسرار وعناوين الصحف ليوم الجمعة 14 كانون الاول 2018