A struggle between authoritarians and liberals in the heart of Europe

The Economist

26 مايو 2018

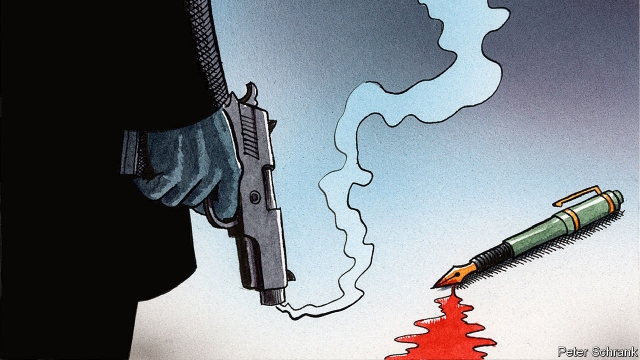

A YOUNG journalist investigating links between his country’s rulers and foreign gangsters is murdered at home by gunshot, alongside his fiancée. The prime minister, who features in the journalist’s reporting, holds a press conference offering to reward anyone who helps bring the killers to justice with €1m ($1.18m) in cash piled up on a table before him. Tens of thousands of demonstrators occupy the streets chanting for justice, but the prime minister, who has previously referred to journalists as “prostitutes” and “toilet spiders”, dismisses them as stooges of opposition parties or foreign speculators. Meanwhile journalists at the public broadcaster are laid off after they protest against the appointment of goverment spokespeople as news managers.

This account of the past few months describes not some dictatorship tipping into chaos but Slovakia, a member of the European Union and NATO. But this is what happened next. The protests lead, after some political wrestling, to the resignation of the prime minister, Robert Fico, and his detested interior minister, Robert Kalinak. Andrej Kiska, the popular president, emerges as a stalwart defender of media freedom, the rule of law and Slovakia’s geopolitical orientation. Academics and journalists rally to the cause of the public broadcaster; the protests continue, albeit in smaller numbers. Far from being cowed by the brutal murder of Jan Kuciak, a journalist at Aktuality, Slovakia’s doughty investigative reporters step up their game.

Two stories; two Slovakias. In Hungary Viktor Orban’s corrupt and autocratic regime seems beyond redemption; in Poland, the giant of the central European Visegrad group (the others are Hungary, the Czech Republic and Slovakia itself), civil society is robust but powerless to stop the government’s assault on the state and judiciary. But in Slovakia the future seems up for grabs. The same is true in the neighbouring Czech Republic, where Andrej Babis, an erratic tycoon facing fraud charges, is struggling to put together a government. The EU is striving for unity in the face of tests from the east, south and across the Atlantic. Here, in the heart of Europe, is a struggle all its own.

After a rocky 1990s under the rule of Vladimir Meciar, a thuggish strongman, Slovakia transformed itself into the workshop of central Europe and quickly got rich (average income is now roughly equal to that of Portugal). It joined the euro zone in 2009. But political progress has been more halting than the economic sort. Mr Fico, a shrewd but cynical operator who ran the country largely uninterrupted after 2006, oversaw a rotten system that shattered trust and weakened institutions. A group of oligarchs became untouchable (their relationships with politicians formed the basis for much of the murdered Mr Kuciak’s reporting). Mr Fico’s nominally social-democratic SMER party has largely served the business interests that helped create it. He has spent the past few years burnishing his pro-European credentials, but some suspect he will now take a populist turn to engineer a return to power—or simply manipulate his replacement, Peter Pellegrini, from his perch as party chairman.

“Something bad has seeped into the very foundation of our nation,” said Mr Kiska after Mr Kuciak’s murder in February, which remains unsolved. Yet Mr Fico’s toppling would have been unthinkable six months ago. The murder, and Mr Fico’s tin-eared response, had an explosive impact, says Grigorij Meseznikov, a political scientist. Matus Kostolny, editor of Denník N, a daily, says the string of scandals his paper and others uncovered used to be ignored. Now, he says, “it’s more and more obvious that the state is not functioning in a normal way.” Ordinary people are suddenly getting in touch to relay stories of graft from years ago. Despite the changes at the top, the new government is a mere “puppet theatre”, says Peter Bárdy, Mr Kuciak’s editor at Aktuality. SMER’s support has slumped to around 20%. The government’s foes may have a vehicle for their grievances in Mr Kiska, who has hinted that he will remain in politics after he steps down as president next year.

Yet Slovakia, and other countries in the region, have known false dawns before. The energy generated in the protests could fizzle now that Mr Fico is out, and there are strong counter-currents at work. Paradoxically, the central European country that has tried hardest to plug itself into the EU’s heart often seems most agnostic about its orientation. A recent survey by GLOBSEC, a Bratislava-based research outfit, found that just 21% of Slovaks believe they belong to the West; by a distance the lowest share in the Visegrad group. These are sobering figures in a country where Russia-inspired disinformation campaigns have found fertile ground, and unsavoury political parties are well placed to exploit them.

The dog days of SMER

As in Hungary, the problems in Slovakia lie less in an ideologically coherent “illiberalism” than in the temptations of embezzlement and nobbled judiciaries. Those fighting for the rule of law look instinctively to Europe for help. Mr Fico’s stance towards Europe may look cynical to some, notes Robert Vass, GLOBSEC’s president, but creating a pro-EU “island” in central Europe bolstered Slovak officials and diplomats, and complicated claims of a fresh east-west divide. Emmanuel Macron in particular has sought to seduce the Slovaks and Czechs to isolate Hungary and Poland.

But there are trends working in the opposite direction. Europe’s interminable refugee rows knit the Visegrad group together. Donald Trump’s America offers succour to central European nationalists. Losing Slovakia would help Mr Orban to consolidate an anti-European regional bloc. This is the test for the generation that took to the streets and toppled Mr Fico. “People are starting to lose their fear,” says Daniel Lipsic, the Kuciak family’s lawyer and a former interior minister. It is a pity that it took the murder of two young people to wake them up.

عن أمل جنبلاط المتجدد: لبنان يستحق النضال

عن أمل جنبلاط المتجدد: لبنان يستحق النضال

صحافيون أم عرّافون!

صحافيون أم عرّافون!

ماذا يجري داخل أروقة بيت الكتائب المركزي؟

ماذا يجري داخل أروقة بيت الكتائب المركزي؟

عن الخرائط التي تُرسم والإتفاقات التي تتساقط!

عن الخرائط التي تُرسم والإتفاقات التي تتساقط!

“الإنحراف في الحياة”/ بقلم كمال جنبلاط

“الإنحراف في الحياة”/ بقلم كمال جنبلاط

هاشتاغ #صار_الوقت يحل أولاً في حلقة جنبلاط

هاشتاغ #صار_الوقت يحل أولاً في حلقة جنبلاط

طاولة نقاش عن أزمة الصحافة في جامعة AUST

طاولة نقاش عن أزمة الصحافة في جامعة AUST

عبدالله: ليظهر لنا وزير مكافحة الفساد حرصه في صفقات البواخر والفيول

عبدالله: ليظهر لنا وزير مكافحة الفساد حرصه في صفقات البواخر والفيول

عبدالله: غريب أمر وزارة مكافحة الفساد!

عبدالله: غريب أمر وزارة مكافحة الفساد!

Comment to Uri Avnery: How Sad What Is Looming Ahead

Comment to Uri Avnery: How Sad What Is Looming Ahead

“Not Enough!”

“Not Enough!”

… لمن لم يقرأ يوسف البعيني/ بقلم وسام شيّا

… لمن لم يقرأ يوسف البعيني/ بقلم وسام شيّا

كمال جنبلاط في مولده الأول بعد المائة: تعاليمه وأفكاره ما زالت الحلّ/بقلم عزيز المتني

كمال جنبلاط في مولده الأول بعد المائة: تعاليمه وأفكاره ما زالت الحلّ/بقلم عزيز المتني

رئيس حزب/ وليس (… سابقاً)/ بقلم د. خليل احمد خليل

رئيس حزب/ وليس (… سابقاً)/ بقلم د. خليل احمد خليل

التوازن السياسي في لبنان

التوازن السياسي في لبنان

لبنان… مشاريع انقلابية مؤجلة

لبنان… مشاريع انقلابية مؤجلة

جنبلاط وحَمَلة أختام الكاوتشوك

جنبلاط وحَمَلة أختام الكاوتشوك

Le Liban est un symbole de tolérance

Le Liban est un symbole de tolérance

Our Automated Future

Our Automated Future

The True Origins of ISIS

The True Origins of ISIS

Les Misérables vs. Macron

Les Misérables vs. Macron

عذراً أيها المعلم/ بقلم مهج شعبان

عذراً أيها المعلم/ بقلم مهج شعبان

رساله الى المعلم / بقلم ابو عاصم

رساله الى المعلم / بقلم ابو عاصم

إلى روح القائد والمعلم كمال جنبلاط/ بقلم أنور الدبيسي

إلى روح القائد والمعلم كمال جنبلاط/ بقلم أنور الدبيسي

أسرار وعناوين الصحف ليوم الجمعة 14 كانون الاول 2018

أسرار وعناوين الصحف ليوم الجمعة 14 كانون الاول 2018