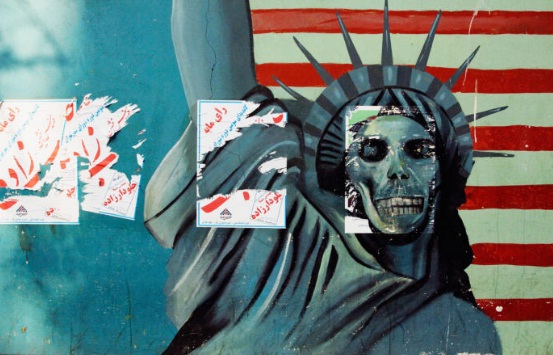

Trump And Iran: Yet Another Hostage Crisis

Robin Wright / New Yorker

7 يناير 2017

Short of last-minute diplomacy, Donald Trump will inherit another hostage crisis with Iran on Inauguration Day—thirty-five years after the first hostage drama at the U.S. Embassy in Tehran ended, as Ronald Reagan was sworn in, and exactly one year after the Obama Administration’s swap to free five more Americans. The Islamic Republic has quietly arrested more Americans since the nuclear deal went into effect, in January, 2016, which coincided with a separate U.S. payment of $1.7 billion, transferred in three planeloads of cash, to settle a legal case from the Shah’s era. The deals were designed to curtail Tehran’s cyclical seizure of Americans, which had been a problem for both Bush Administrations, too.

Only they didn’t. At least six Americans and two green-card holders are now imprisoned or have disappeared in the Islamic Republic. One is now the longest-held civilian hostage in U.S. history. An undisclosed number have not been publicly identified.

Under President Trump, U.S. strategy on Iran was already likely to face a major overhaul. During the campaign, he vowed to “set fire” to the nuclear pact, which he called “the worst deal ever negotiated”—a view he repeats regularly in angry tweets. “My No. 1 priority is to dismantle the disastrous deal with Iran,” he told the American Israel Public Affairs Committee, in March. “I have been in business a long time. I know deal-making and, let me tell you, this deal is catastrophic—for America, for Israel, and for the whole Middle East.” The United States, he has urged since then, “should double up and triple up the sanctions.”

Two weeks away from Trump’s Inauguration, almost two-thirds of Americans oppose pulling out of the Iran nuclear deal or trying to renegotiate it, according to a survey released Wednesday by the University of Maryland’s Program for Public Consultation, which has done extensive polling in the United States and Iran in recent years. “Though President-elect Trump campaigned on ripping up the deal and seeking to negotiate a better one, the majority of Americans would rather continue with the deal as long as Iran continues to comply with its terms,” Steven Kull, the program’s director, said in a statement.

But the top trio in Trump’s foreign-policy team goes even further than the President-elect on a new Iran policy. All three have supported ousting the theocracy, even though U.S. intelligence officials concluded a long time ago (woe to them now) that the regime will be around for the foreseeable future. “Regime change in Tehran is the best way to stop the Iranian nuclear-weapons program,” Michael Flynn, the new national-security adviser and the former director of the Defense Intelligence Agency, told the House Foreign Affairs Committee, in 2015. After the 2012 attack in Benghazi, Flynn insisted that Iran was responsible and ordered D.I.A. staff members to find evidence to prove it. They couldn’t. U.S. intelligence ultimately blamed local militants.

In “The Field of Fight,” a book published in July, Flynn and his co-author, Michael Ledeen, described Iran as the head of a global alliance focussed on the United States. “We face a working coalition that extends from North Korea and China to Russia, Iran, Syria, Cuba, Bolivia, Venezuela, and Nicaragua. We are under attack, not only from nation-states directly, but also from al Qaeda, Hezbollah, ISIS, and countless other terrorist groups,” they wrote. Iran “is the linchpin of the alliance, its centerpiece,” they continued. The United States is involved “in a world war, but very few people recognize it.”

James Mattis, the nominee for Defense Secretary and a retired Marine general, has a grudge against Iran dating back to the 1983 Marine bombing in Beirut. “For all the talk of isis and Al Qaeda everywhere right now,” Mattis said in April, “nothing is as serious . . . in terms of stability and prosperity and some hope for a better future for the young people out there than Iran.” When he was the chief of U.S. Central Command, Mattis added, “every morning, I woke up, the first three questions I had had to do with Iran and Iran and Iran.”

Mike Pompeo, Trump’s choice for the next C.I.A. chief and a Kansas Republican who served on the House Select Committee on Intelligence, led the campaign against the Iran nuclear deal on the Hill. “This deal allows Iran to continue its nuclear program. That’s not foreign policy; it’s surrender,” he said the day it was announced. Afterward, in a political stunt, Pompeo and two other congressmen applied for visas to Iran, to observe the February, 2016, parliamentary elections. They demanded the right to inspect Iranian nuclear facilities, talk with U.S. detainees, and meet with officials about the Revolutionary Guards’ overnight detention of American sailors who had drifted into Iranian waters. On the one-year anniversary of the six-nation pact with Tehran, Pompeo wrote on Foxnews.com, “Congress must act to change Iranian behavior, and, ultimately, the Iranian regime.”

The nuclear deal may not be the first flashpoint between the Trump Administration and Iran, since the world’s five other major powers are also signatories. They won’t walk away. The focus may instead be bigger—spurred by another hostage crisis, a move by congressional Republicans to impose new sanctions, or a flare-up in the sporadic tensions between the U.S. Navy and the Revolutionary Guards in the Persian Gulf. Obama has repeatedly demonstrated strategic patience on Iran; Trump has a shorter fuse.

The unravelling is already visible. In an overwhelming vote on November 17th, Republicans in Congress moved to block Iran’s purchase of eighty Boeing passenger planes—a deal worth some sixteen billion dollars and, Boeing claims, tens of thousands of jobs. “The world’s greatest state sponsor of terror should not be aided by the U.S. taxpayer, by our banking system, in order to finance planes that we really don’t know [what] they’re going to do with them,” Bob Dold, an Illinois Republican, said on the House floor. The initiative fell short, after the White House pledged to veto a law if it passed the Senate, warning that “the sweeping and vague nature of this provision would have a chilling effect on U.S. and non-U.S. entities seeking to engage in permissible business with Iran.”

The new Republican-weighted Congress will almost certainly try to block the Boeing deal again—and Trump will face a tough call, given the jobs it will support. In June, a campaign statement pledged that, under a Trump Presidency, “the world’s largest state sponsor of terror would not have been allowed to enter into these negotiations with Boeing.” Congressional Republicans have been itching to impose sanctions on Iran for other issues, including missile tests, support for terrorist groups, and human-rights abuses. The latest hostage crisis may spur them on.

As more Americans were picked off the streets in Iran, Secretary of State John Kerry pressed their cases in every conversation this year with his Iranian counterpart, so far to no avail, U.S. officials told me. The secret back channel between the State Department and Iranian intelligence ended after the last swap.

Many cases have gone unreported for months. Iranian intelligence and the Revolutionary Guards—who make their own arrests—tell detainees that they have a better chance of release if their families don’t publicize their cases, former prisoners and their families told me. Relatives and governments work—sometimes fruitlessly—in secret. Meanwhile, detainees endure daily interrogations, former prisoners told me. Some have been sentenced to long prison terms on spurious charges of undermining the regime and its values.

“We will use all legal and diplomatic means within our disposal to bring our detained and missing U.S. citizens home,” a senior Administration official told me. “We are often constrained from publicly sharing information on these cases and will not discuss ongoing diplomatic efforts, but this does not indicate the absence of action or progress.”

The case of Karan Vafadari, a graduate of New York University, is the latest to come to light. He was arrested in July; his family finally announced his detention in December. He has three children who live in the United States. His wife, Afarin Niasari, a green-card holder, was arrested first, at Tehran’s international airport, as she was leaving for a family wedding abroad. She was told to call her husband and ask him to go to the airport, where he was detained, Hadi Ghaemi, of the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran, told me. The couple, who run an art gallery in Tehran, are members of the Zoroastrian faith, one of the world’s first monotheistic religions and a minority with a long history in Iran. Vafadari’s sister, who lives near Washington, D.C., released an appeal to the government this month.

Several cases involve Americans of Iranian descent visiting family members who stayed behind in Iran. Gholamrez (Robin) Shahini, who lives in San Diego, was picked up in July, six weeks after he flew to visit his ailing mother. He was detained in the northeast city of Gorgon, near the Caspian Sea, as he walked to a restaurant with friends. He was swiftly convicted, in a secret trial, of espionage and “collaboration with a hostile government” and sentenced to eighteen years.

After those three cases, in July, the State Department issued a travel warning, in August. “Iranian authorities continue to unjustly detain and imprison U.S. citizens, particularly Iranian-Americans, including students, journalists, business travelers, and academics, on charges including espionage and posing a threat to national security,” it advised. “Iranian authorities have also prevented the departure, in some cases for months, of a number of Iranian-American citizens who traveled to Iran for personal or professional reasons.”

Three cases are holdovers left unresolved by the last swap. Siamak Namazi, an Iranian-American business consultant who holds degrees from Tufts and Rutgers, was detained while visiting his parents, in October, 2015. Namazi was not included in the January, 2016, swap because his family opted out, fearful that the deal would not go through or that association with the U.S. government would taint him, U.S. officials and Iranians close to the case told me.

Their decision backfired. In February, Namazi’s father, Baquer Namazi, was the first of the new crop of Americans to be detained. Baquer, a former unicef official who served in African crisis zones, is now eighty. In October, the father and son were sentenced, in a closed court session that reportedly lasted only a few hours, to ten years in prison on charges of spying for the United States.

عن أمل جنبلاط المتجدد: لبنان يستحق النضال

عن أمل جنبلاط المتجدد: لبنان يستحق النضال

صحافيون أم عرّافون!

صحافيون أم عرّافون!

ماذا يجري داخل أروقة بيت الكتائب المركزي؟

ماذا يجري داخل أروقة بيت الكتائب المركزي؟

عن الخرائط التي تُرسم والإتفاقات التي تتساقط!

عن الخرائط التي تُرسم والإتفاقات التي تتساقط!

“الإنحراف في الحياة”/ بقلم كمال جنبلاط

“الإنحراف في الحياة”/ بقلم كمال جنبلاط

هاشتاغ #صار_الوقت يحل أولاً في حلقة جنبلاط

هاشتاغ #صار_الوقت يحل أولاً في حلقة جنبلاط

طاولة نقاش عن أزمة الصحافة في جامعة AUST

طاولة نقاش عن أزمة الصحافة في جامعة AUST

عبدالله: ليظهر لنا وزير مكافحة الفساد حرصه في صفقات البواخر والفيول

عبدالله: ليظهر لنا وزير مكافحة الفساد حرصه في صفقات البواخر والفيول

عبدالله: غريب أمر وزارة مكافحة الفساد!

عبدالله: غريب أمر وزارة مكافحة الفساد!

Comment to Uri Avnery: How Sad What Is Looming Ahead

Comment to Uri Avnery: How Sad What Is Looming Ahead

“Not Enough!”

“Not Enough!”

… لمن لم يقرأ يوسف البعيني/ بقلم وسام شيّا

… لمن لم يقرأ يوسف البعيني/ بقلم وسام شيّا

كمال جنبلاط في مولده الأول بعد المائة: تعاليمه وأفكاره ما زالت الحلّ/بقلم عزيز المتني

كمال جنبلاط في مولده الأول بعد المائة: تعاليمه وأفكاره ما زالت الحلّ/بقلم عزيز المتني

رئيس حزب/ وليس (… سابقاً)/ بقلم د. خليل احمد خليل

رئيس حزب/ وليس (… سابقاً)/ بقلم د. خليل احمد خليل

التوازن السياسي في لبنان

التوازن السياسي في لبنان

لبنان… مشاريع انقلابية مؤجلة

لبنان… مشاريع انقلابية مؤجلة

جنبلاط وحَمَلة أختام الكاوتشوك

جنبلاط وحَمَلة أختام الكاوتشوك

Le Liban est un symbole de tolérance

Le Liban est un symbole de tolérance

Our Automated Future

Our Automated Future

The True Origins of ISIS

The True Origins of ISIS

Les Misérables vs. Macron

Les Misérables vs. Macron

عذراً أيها المعلم/ بقلم مهج شعبان

عذراً أيها المعلم/ بقلم مهج شعبان

رساله الى المعلم / بقلم ابو عاصم

رساله الى المعلم / بقلم ابو عاصم

إلى روح القائد والمعلم كمال جنبلاط/ بقلم أنور الدبيسي

إلى روح القائد والمعلم كمال جنبلاط/ بقلم أنور الدبيسي

أسرار وعناوين الصحف ليوم الجمعة 14 كانون الاول 2018

أسرار وعناوين الصحف ليوم الجمعة 14 كانون الاول 2018